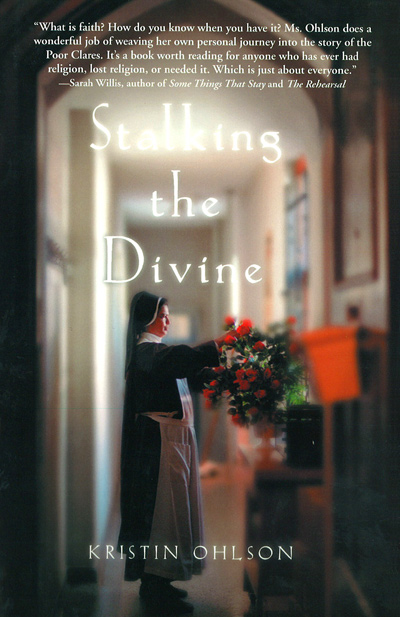

In Stalking the Divine, a Cleveland woman attends Christmas Mass at an old city church seeking holiday cheer and comfort in the trappings of a faith she abandoned more than 30 years ago. Instead, she finds a tiny threadbare congregation and a nearly forgotten group of aging, cloistered, contemplative nuns with a mission to pray day and night for the sorrows of the world. Thus begins a three-year dialogue between the nuns and Kristin Ohlson, who struggles to understand how these women gave up the world--and continue to do so joyfully--for their faith. Ultimately, Ohlson finds that talking to the nuns becomes a way of opening herself up to the possibility of the sacred--which is, in its way, an answered prayer.

The Story Behind the Book

My writing life has always cleaved roughly in two: for the most part, I’ve been interested in writing (and reading) long fiction and short nonfiction. Writing the short nonfiction pieces was my way to learn about the world—whether I was struggling to understand how scientists fuse the genetic material from lightening bugs with that of zebrafish and create a little Frankenfish that glows in the presence of water toxins…or learning about the special sorrows that women coming out of prison face…or grappling with astrophysics’ most daunting questions about the lifespan of matter—my world became larger with each article. But I never was willing to give myself over to a long piece of nonfiction—in other words, a book—because I wasn’t willing to stick with one topic for more than a few months.

Then I stumbled upon St. Paul Shrine here in Cleveland and the Poor Clares of Perpetual Adoration and everything changed. I had been raised Catholic, but bolted from faith as a teenager and was a scornful atheist during my twenties and thirties. By the time I was into my forties, I began to yearn for faith: I wanted a steadying hope after my 22-year marriage had ended, after a new one had begun, after my children had the audacity to grow up and my parents the audacity to grow old, after I had sensed that whatever I thought I knew of the world wasn’t enough. During most of my life I had considered faith a kind of sickness, something that softened the brain and allowed the soothing delusion of divine power. Now I wanted faith, but I wasn’t sure if I hadn’t inoculated myself against it for good.

I continued going to Mass at St. Paul Shrine, huddling in the shadows at the back of the church and peering curiously at the faithful—then realized I wanted to write about the nuns. People who like to write generally do so because it gives them a way to explore and understand things, whether these things are out in the world, buried in the vault of their own memory, or have sprung unbidden from their imagination. In my case, I hoped that writing about the nuns might help me construct a framework for trying to make sense of their faith and, perhaps, learn to build some kind of faith of my own. So Stalking comprises two stories: mine and theirs.

When I told one of my oldest and dearest friends that I was writing a book about the Poor Clares, he threw up his hands in exasperation at my seemingly hopeless attraction to failure and snapped, “Who’s going to want to read about a bunch of old women who don’t have sex?” Despite reactions like that, I had an idea that there were other people like me— people whose lives had a secular sheen but who yearned for something else, who wondered if there was a divine pulse behind it all.

I suppose writing a book, any book, changes you--you think about things and think about them and carry them around in your head for weeks. They carve new shapes in your mind. I seem to have emerged from writing this book with a new appreciation for stillness. As I sat in the Poor Clares’ big old monastery week after week, I grew to like the sounds of its silence all around me. I felt their tremendous striving in the silence and also their waiting—a form of striving, of holding themselves back from anything that might distract them from God. I was one of those distractions, and they put up with me graciously. And then it ended, when each had answered my questions about prayer and commitment and a life of faith, and, perhaps, when I had discovered the limitations of the questions.